‘Universo Lorca’ in the Parque de las Ciencias Planetarium in Granada

While living in Granada for three months between Nov 1998 and Jan 1999, I attended dozens of events celebrating the 100th anniversary of Lorca’s birth. I became obsessed with a show of his drawings, poetry and music show at the local planetarium. The opening of the event was delayed by the holidays and I went every day for weeks asking when it would open. Finally the guards who were used to seeing me, greeted me with big smiles and told me the date. It was amazing to sit back in the chair and watch his drawings and lines of poetry interact with the stars. Later living in Santa Fe I was able to work with the Santa Fe Opera to bring the exhibit there to celebrate a world premier of an opera based on Lorca’s life.

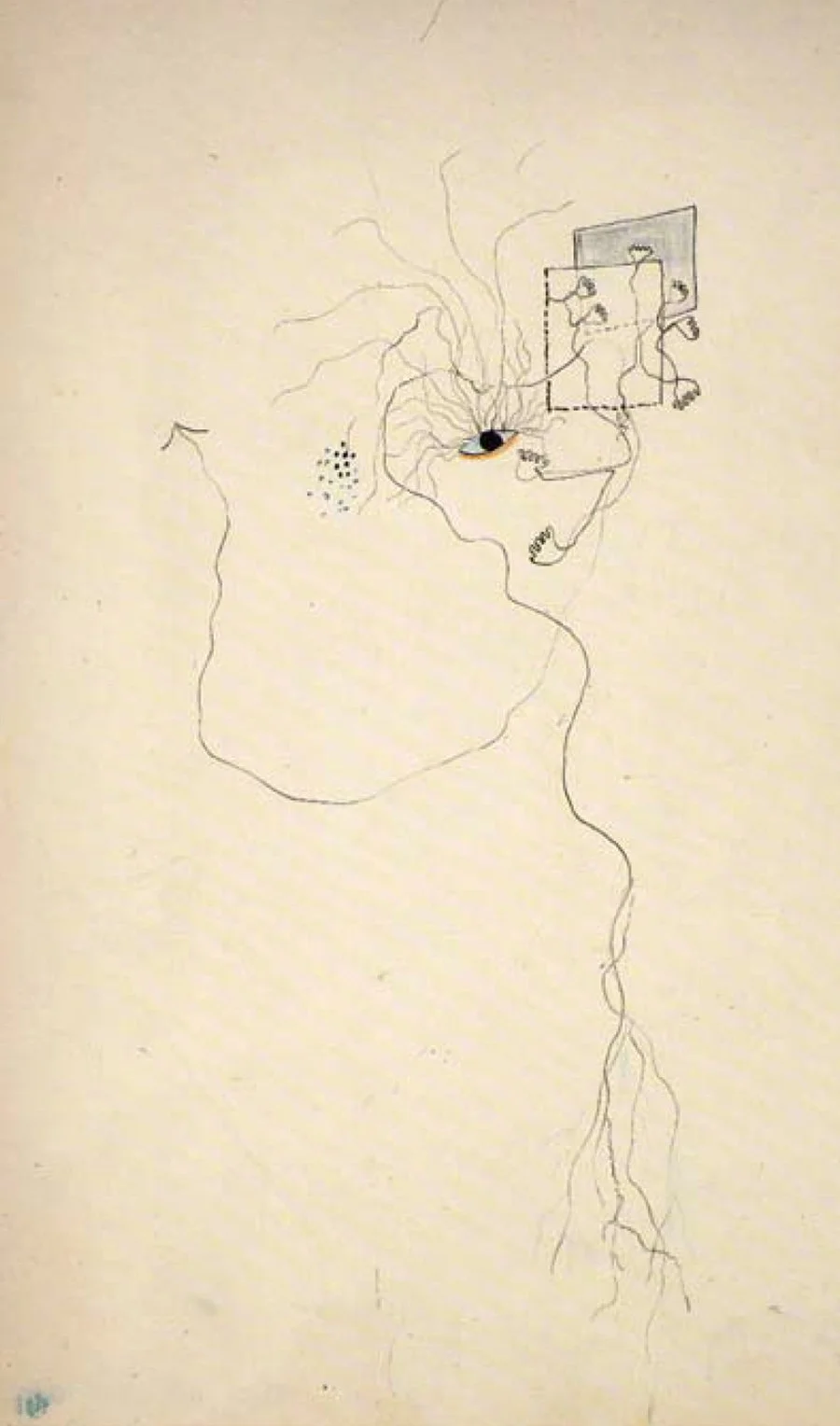

Lorca Drawing

There is no evidence that Lorca and Cajal met. However, they did hang out in the same cafes. They did have a similar circle of friends. Lorca would have been a young wiper-snapper and Cajal a Noble Prize winner and de-facto head of the Residencia de estudiantes, think of him as the ultimate Resident Adviser.

The overall question of the influence of Santiago Ramon y Cajal on Federico Garcia-Lorca and specific questions like did they meet and how directly did the drawings Ramon y Cajal play in shaping how Garcia-Lorca drew are addressed in the book “New Lenses for Lorca: Literature, Art, and Science the Edad de Plata,” by Cecelia Cavanaugh, published in 2012.

This book began as her doctoral dissertation, led to her living in Spain for a period of time and to direct contact and support of the Ramon y Cajal and Garcia-Lorca families.

Madrid is the physical location of Ramon y Cajal and Garcia-Lorca during the Edad de Plata, or Silver Age but more specifically the Residencia de estudiantes,” or Student’s Residences.

In Lorca’s well-known essay, “Theory and Play of The Duende,” he states, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Between 1918 when I entered the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, and 1928 when I left, having completed my study of Philosophy and Letters, I listened to around a thousand lectures, in that elegant salon where the old Spanish aristocracy went to do penance for its frivolity on French beaches.

Longing for air and sunlight, I was so bored I used to feel as though I was covered in fine ash, on the point of changing into peppery sneezes.

So, no, I don’t want that terrible blowfly of boredom to enter this room, threading all your heads together on the slender necklace of sleep, and setting a tiny cluster of sharp needles in your, my listeners’, eyes.

In a simple way, in the register that, in my poetic voice, holds neither the gleams of wood, nor the angles of hemlock, nor those sheep that suddenly become knives of irony, I want to see if I can give you a simple lesson on the buried spirit of saddened Spain.”